Rotman School of Management Expansion – University of Toronto

When a $93.8-million addition to the Joseph L. Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto opens in September, the focus will be on preparing students for the world of business and finance.

Along with its educational purposes, this steel and curtain-wall building offers a picturesque view of the 19th century buildings that make up the university campus in downtown Toronto. In fact, because of these Victorian structures, extra attention was required in order for the building to integrate with the existing school and its surroundings.

Designed by KPMB Architects to LEED Siler status and built by construction manager Eastern Construction, the addition consists of a nine-storey tower and a two-storey events hall that wraps around an 1880s designated heritage house. The house was renovated and restored by a pre-qualified contractor and will be the headquarters for the PhD program.

Highlighted by a sunken courtyard and atrium, the nine-storey tower houses the Desautels Centre for Integrative Thinking and the Martin Prosperity Institute, seven tiered classrooms that each accommodate 70 students, study spaces and a Business Information Centre with a green room on the fourth and fifth floors. A mix of classrooms and offices make up the first five floors while the sixth to ninth floors, which are stepped back, are comprised of faculty offices, research spaces and PhD units. The ninth floor has a double-height meeting room.

Planting of trees, grasses and shrubs in front of the addition, and particularly the heritage house, provides a contemporary feel to match the architect’s design, says Robert Beaudin, project manager, Janet Rosenberg & Studio, the landscape architect. “It was important for us to support that vision.”

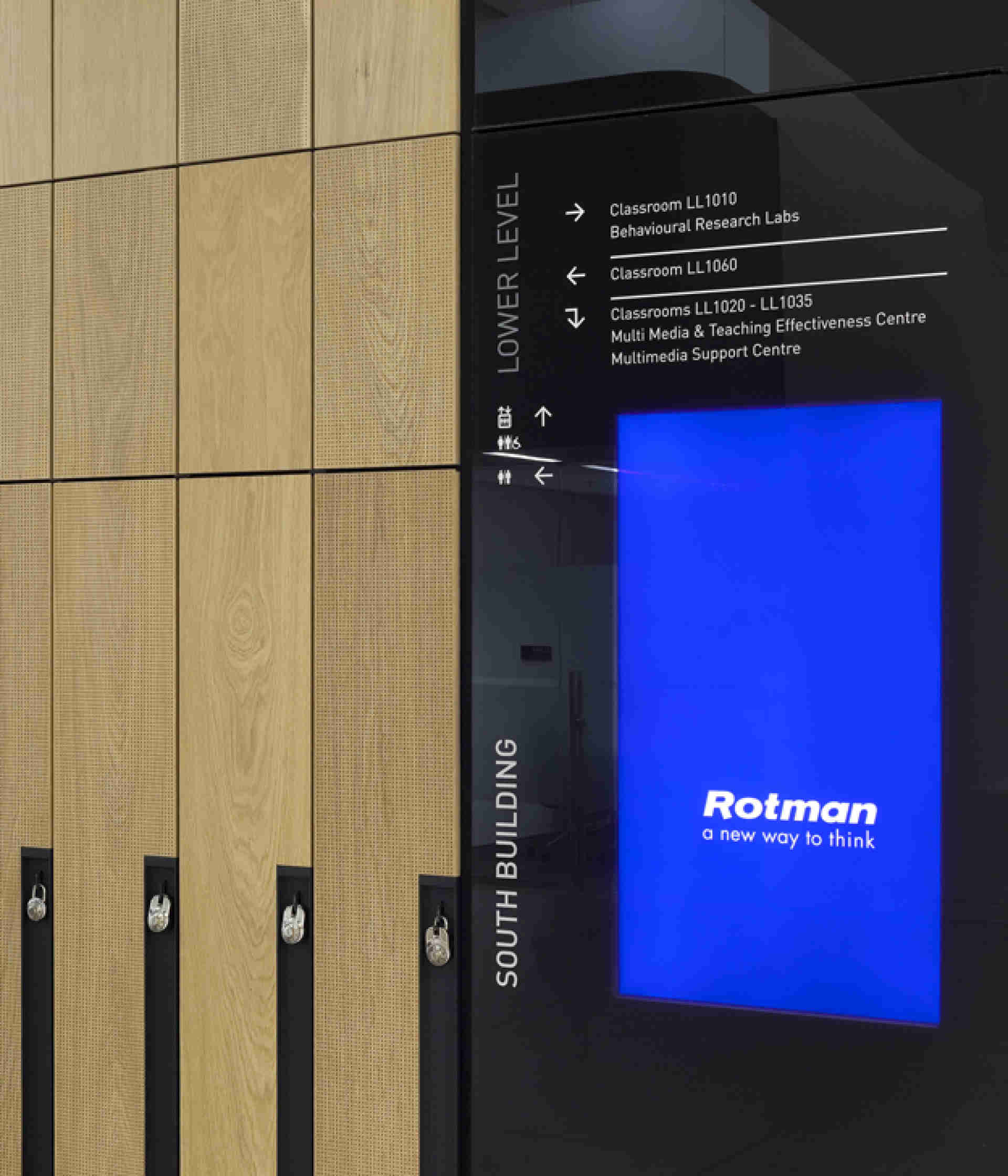

Jutting out from the tower and distinguished by its own green roof, the lower portion of the building features a café, and a 400-seat, 600-square-metre event hall with the latest audiovisual technology features. These state-of-the-art features were designed by Engineering Harmonics Inc., a multidisciplinary consultant specializing in the design of AV materials, digital signage, performance sound and broadcast systems. “The hall is a multipurpose space in the truest sense and has more AV technology than any university meeting space that we know of,” says project director Gary Tibshirani.

With a mandate for quick changeovers between six room configurations the event box is served by 11 10,000-lumen projectors and it was Engineering Harmonics’ task to design a system where that many projectors could be accommodated in the ceiling space.

“There were several other challenges including planning an unobtrusive tracking system in the lecture rooms,” he says. “Business schools often record lectures and our team was challenged to find an elegant solution to automatically track professor movements between the teaching station and the white boards.”

After reviewing various methods of tracking such as under-carpet and body-worn sensors, Engineering Harmonics concluded that infrared technology was less restrictive. With the deployment of proximity sensors, it designed a camera tracking system that gives lecturers “the freedom to move across the full width of the room allowing cameras to capture facial expressions at all times.”

Both interior and exterior lighting is designed to complement the architecture of the spaces while meeting LEED energy targets, says Simon Aspinwall, principal with Smith + Andersen, the electrical/mechanical consultant. The lighting is controlled through a low-voltage control system along with localized scene controllers within the classroom and other key spaces, says Aspinwall.

The roots of the expansion go back to 2006 when the university decided that the existing building was no longer adequate to meet the school’s needs, says Brian Szuberwood, the university’s associate director of capital projects. “Even with a couple of additions, some programs and departments had to be dispersed throughout the campus and just beyond the fringe of the campus.”

Although there was selective demolition of the rear of the 1880s heritage house and total demolition of another house, the main footprint of the addition was constructed on what was a university-owned parking lot. In that respect, the development was fairly straightforward. Bu the new building also has 100 per cent lot coverage and abuts the university’s Massey College, Innis College, Trinity College and Newman Centre. “We have construction licence agreements with our neighbours [the colleges],” says Szuberwood. “That protects them as well as us.”

Due to the proximity of the buildings, a caisson wall shoring wall system was installed all around the excavation site, explains Jim Broomfield, Eastern Construction’s senior project manager.

That list of neighbours included the existing school that had to remain open throughout the schedule. Eastern had to ensure its work did not interfere with day-to-day operations, says Broomfield.

Adhering to that non-interference condition necessitated a number of planning strategies and actions such as only constructing the corridors that link the two buildings in the summer. “The Rotman School undertook a communication program to advise staff and students of construction activities,” he says.

Traffic control was also an issue in the surrounding area, especially on St. George St., where pedestrian traffic is heaviest. Hoardings and covered ways that were erected to protect exit routes and construction were closely monitored to ensure safety. “Space was the major logistical issue from beginning to end,” says Broomfield. A major amount of staff time was spent on controlling and scheduling of excavation and concrete trucks to avoid logjams on site.

A just-in-time approach had to be implemented since there was minimal storage space. Materials had to be dropped and immediately moved to work areas using a man hoist or a tower crane. The tower crane was used extensively for hoisting activities and was in operation six days a week. Curtain wall panels, for example, were delivered and hoisted on Saturdays.

But the major challenge throughout the three-year-long undertaking was the aggressive schedule and architectural details that required much coordination. The project was also held up by a City of Toronto workers’ strike which delayed issuance of a shoring permit. At the same time, the university’s requirement for the school to be opened by September 2012 had to be met. At the peak of the project, which extended from September to December 2011, there were about 150 workers on site, says Broomfield.

Despite the aggressive schedule and the various hurdles along the way, the university was able to take advantage of some competitive material pricing. As a result, it added several enhancements to the original project scope without increasing the construction budget, says the university’s Brian Szuberwood. Those features included refurbished windows and a more sympathetic and historically accurate slate roof on the PhD heritage house. “The house originally had a slate roof, but was later replaced with asphalt shingles.”